The following is copyrighted material from an upcoming book on Scagliola, and cannot be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the author, James Gloria.

Certainly there were finishes imitative of marble since antiquity using paints and plasters. However, the unique mixture of highly-polished, marbled plaster is generally attributed to 17th century Italian monks, Guido Fassi being the most prominent. Fassi and others produced incredibly detailed inlaid panels for altar fronts and tables. While these intricately inlaid surfaces may have begun in imitation of Pietra Dure, Scagliolists quickly took advantage of the infinite variety of color, plasticity and patterns only possible with plaster. The ease with which it is carved enables incredible renderings of fine lace, delicate flowers and the interwoven tendrils of grottesca designs . By the early 17th c., the panels of Fassi, Enrico Hugford and others practically exploded with Rococo arabesques, trompe l’oeil maps and finely-crosshatched renderings of saints.

From northern Italy the technique spread throughout much of Switzerland and Germany. ( In fact, some say that it may have arisen simultaneously in these places) and the rest of continental Europe, eventually making its way to England by way of the architects Robert & James Adam. By then, the technique was adapted for more monumental architectural purposes: sheathing columns, walls and even floors, most notably in Syon House, designed by Robert Adam. These broader marbling techniques are usually called “stucco marmo”, (marbled stucco) to distinguish them from the more intimately scaled, inlaid scagliola panels. The British also introduced a new material, Keene’s Cement, to meet the demands of scale and institutional wear. Much harder than regular plaster of Paris, it could be polished to a high sheen and would better resist the scuffs and scratches of public architecture.

In making its way to the new world, the technique acquired another approach under the moniker, “marezzo”. This strictly Anglo-American process is a further variation where patterns could be  created more quickly using raw silk as a patterning material. This suited the scale of the public spaces where it was primarily used; in the U.S. Capitol, U.S. patent office and a dozen other state capitols, not to mention movie theaters, hotels and houses of worship. (Willard Hotel Scagliola columns pictured left, Washington, D.C.)

created more quickly using raw silk as a patterning material. This suited the scale of the public spaces where it was primarily used; in the U.S. Capitol, U.S. patent office and a dozen other state capitols, not to mention movie theaters, hotels and houses of worship. (Willard Hotel Scagliola columns pictured left, Washington, D.C.)

But the quality of the Scagliola produced in the period of the Industrial Revolution was compromised by the early 20th c. In an article published in Architectural Forum in 1929, Clifford Wayne Spencer wrote: “No art has been subjected to greater abuse at the hands of the modern commercial competitive system than has the making of artificial marble...” His premise was that the clumsy, aesthetically-challenged attempts at scagliola by inferior craftsmen had cheapened the reputation of the technique. At the same time, these plasterers undercut the prices of legitimate artisans effectively pushing the best craftsmen out of work while leaving examples of Scagliola undeserving of its heritage.

It was not until the 1970’s that a revival of the technique in America took hold. In an article for the Association for Preservation Technology, Alfred Staehli describes how the bombing in the City Hall rotunda in Portland Oregon created a new appreciation for the technique:

The persons who placed the explosives in the East Portico under the bell inadvertently caused the preservation of the art of making scagliola through the training of a younger generation of Portland plasterers in the old art necessary to the restoration of the City hall.

According to Staehli, the information was passed on by an aging plasterer, Al Hanson, who had witnessed the making of Scagliola as a young tradesman during his early years as an apprentice in the 1920‘s. His connection to the past enabled for the training of a new generation of restorers.

And many restorations followed, as the technique was discovered in courthouses, theaters, churches and government buildings throughout the U.S. Indeed, no corner of the country seem to have escaped the artisan’s touch. In 2002 I traveled to Grafton, West Virginia to consult on the restoration of the waiting room of the main rail station. With its simply-designed, marezzo columns and wainscoting, this was the first large-scale American Scagliola I had seen, and the effect was impressive even in its degraded state.

My Scagliola Geneology

My connection to the European tradition starts with San Servolo. The thread of craftsmen begins north, with an unknown craftsman in East Germany. In 1957, he was the mentor of Manfred Siller, a young plasterer who travelled there to study with this now unknown Scagliolist. Siller eventually went on to work with him. Patrick Tranquart met Siller 26 years later, when Siller was the first Scagliola instructor at San Servolo. The two had met in 1983, and Tranquart was enchanted by the technique. An able student, he went far and completed many commissions throughout Europe, and America. He eventually replaced Siller as the instructor at San Servolo.

My first teacher, Walter Cipriani, studied with Tranquart in San Servolo, followed by study with Olympia Serafin at the Accademia Caerite. It was there that I received my first instruction.

My interest in further study brought me to San Servolo in 2003, when the program was under the direction of Patrick Tranquart. In a two-week intensive, Tranquart reinforced what I had learned from Olympia Serafin and Walter Cipriani in Ceri. But more importantly, Tranquart introduced me to the technique of “Stucco Marmo”, the process of applying scagliola to walls and columns.

[{readmore:More|readon}]

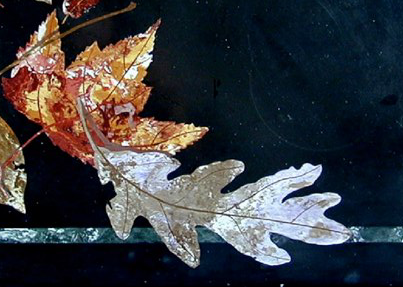

As a scenic artist-come-mural painter and faux finisher, I have a skeptical eye for faux marble. This panel had the black, glossy, smoothness of Belgian Black, the favored background for Italian “Pietra Dura” inlaid marble. Into the surface was carved a simple flower in delicate colors. The finish revealed no traces of brush strokes, deliberate veining, or any of the other telltale signs of a faux finish. The panel was cool to the touch, just like marble. Yet, had it been real stone, it would have had seams where the inlaid pieces joined. I asked the director what it was and she replied by inviting me to come to Italy and study the technique.

As a scenic artist-come-mural painter and faux finisher, I have a skeptical eye for faux marble. This panel had the black, glossy, smoothness of Belgian Black, the favored background for Italian “Pietra Dura” inlaid marble. Into the surface was carved a simple flower in delicate colors. The finish revealed no traces of brush strokes, deliberate veining, or any of the other telltale signs of a faux finish. The panel was cool to the touch, just like marble. Yet, had it been real stone, it would have had seams where the inlaid pieces joined. I asked the director what it was and she replied by inviting me to come to Italy and study the technique.